It all started for the band back in the mid-1980s, when Lawler and the two Hogan brothers met as teenagers growing up in Limerick – and, sharing a love for groups like the Cure and the Smiths, decided to try their hand at rock music. Initially, they formed a quartet with a male singer, though after six months, in early 1990, he left – at which point he suggested his girlfriend’s friend, who came from Ballybricken, a small town outside Limerick, as a replacement.

When Dolores came to audition for them, a rural girl suddenly among city boys, she was “quiet as a mouse”, as Noel recalls – until she sang, that is. “We were immediately, blown away,” says Mike. “Her voice was something special.” Dolores, in turn, was enamoured by the boys. “I really liked what I heard; I thought they were nice and tight,” she later recalled. “It was a lovely potential band but they needed a singer – and direction.” There was no question that they had found their new fourth member.

The band gained not only a compelling frontwoman but a brilliant musician. From a young age, Dolores learnt classical piano, and played piano, and harmonium in her local church, as well as singing in the choir. “I used to go from school to piano lessons to home and maybe I’d have to go to church and then I might have some homework and go to bed,” she said, of her early years routine. When she was 17, she then taught herself guitar. But above and beyond her training, she had an “amazing ear”, says Noel. “She was streets ahead of the rest of us in the beginning, but that was a good thing. It forced all of us to up our game.”

As songwriters, Noel and Dolores gelled immediately, while finding their own particular way of working. From the very beginning, they never wrote in the same room together. Back then, Noel would lay down guitar parts on cassette which he’d then give to Dolores to develop verses and chorus around in her own space and time. For the first two years of the band, they wrote like crazy, Noel recalls. “It was that thing where you’ve found somebody that you clicked with, and you wanted to get as much as you could out of that.”

At the same time, after their demo of ‘Linger’ did the record company rounds over in London, they quickly became the talk of the industry. In the summer of 1991, following a gig at the University of Limerick which was also attended by 32 A&R men, they signed to Island Records. The reason they chose the celebrated label was because of Denny Cordell, the legendary record producer who was at that time Island’s A&R. Seeing their long-term potential, he promised to allow the band the chance to develop at their own pace and suggested they get some touring under their belt in the first instance.

The following year, they then began recording their debut album Everybody Else is Doing It So Why Can’t We? with producer Stephen Street. Street had worked with The Smiths and Blur, as well as co-writing Morrissey’s first solo album Viva Hate, and so his involvement was a dream come true. He has subsequently taken the reins on four further albums with them, including In the End. Noel credits him with helping to create the sweepingly epic Cranberries sound. “What happened was not just down to the songs – the production had a lot to do with it.”

The album’s title was Dolores’ creation, as every album title was; it expressed perfectly their determination to succeed. “Elvis wasn’t always Elvis,” she said, explaining its meaning. “He wasn’t born Elvis Presley, he was a person who was born in a random place. Why shouldn’t a band from a small city in the Southwest of Ireland get signed, conquer the world, and make a great record?”

And conquer they did. The success of Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? remains remarkable. After being released in the UK in March 1993, the album really took off a few months later when Linger was picked up by college radio in America and the band subsequently toured across the Atlantic. It would go on to hit no 1 in both Ireland and the UK, and sell more than six million copies worldwide. From the heart-wrenching Linger, a song inspired by Dolores’ first kiss, to the giddy Dreams, it managed to convey the highs and lows of young love with a rare purity and tenderness.

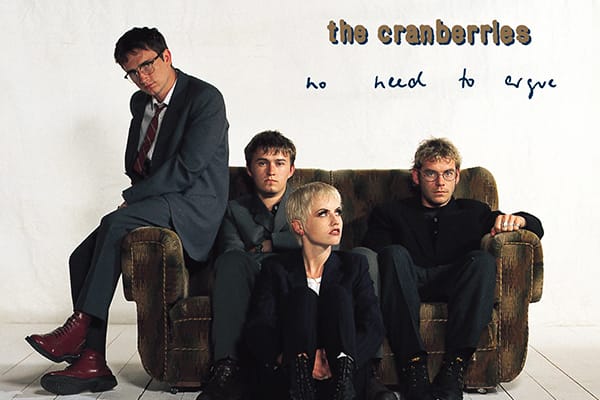

After that, no one would have expected Zombie: the lead off single from 1994’s second album, No Need to Argue, and an era-defining howl of rage. Inspired by the IRA Warrington bombings, which left two boys dead, it saw Dolores fiercely decrying the violence of the Irish conflict over distorted, hard-rock guitars. “This song is our cry against man’s inhumanity to man, inhumanity to child. And war, babies dying, and Belfast, and Bosnia, and Rwanda,” she explained at the time. “It was a turning point for us,” recalls Noel. “I always remember the day she came in with it. We were in a tiny little shed in Limerick, where we were rehearsing. She came in and started playing it on acoustic guitar and we played along but she was like ‘no this needs to be heavy, it’s an angry song, and it needs to reflect that.’”

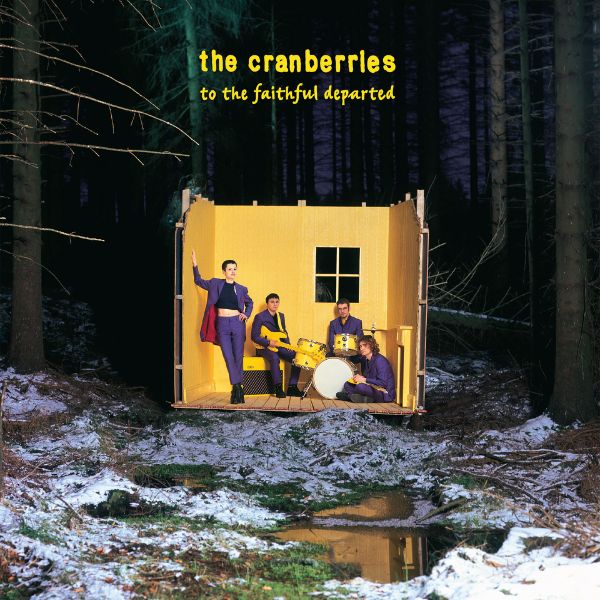

As well as having an immense cultural impact, it was transformative for the band musically. “We learned from that song that you can actually do a lot with that aggression – and particularly live, it made a massive difference to us, because we became this loud, anthemic band all of a sudden,” says Noel. They carried both its harder sound and wider lyrical focus onto their third album, 1996’s To the Faithful Departed.

Two more albums followed, 1999’s Bury the Hatchet and 2001’s Wake Up and Smell the Coffee, whose maturing outlook reflected their life experiences: “Animal Instinct”, on Bury the Hatchet, for example, saw Dolores powerfully evoke her experience of new motherhood. By 2003, all four of the band were ready for a break, after a relentless decade of recording and touring, and so they went on hiatus, with each pursuing their own separate musical projects.

But after the band reunited for a world tour in 2009, they found themselves re-energised, and so returned to creating new material again. Their next album, 2012’s Roses, was an especially atmospheric collection, which incorporated new textures into their sound. “Because we’d all gone off in different directions, we all came back into the band with these new experiences and a new way of working and it was great,” says Noel. “It was a real buzz to do that album.” Among its highlights was the otherworldly title track, which Dolores wrote in memory of her late father, who died in 2011 and was one of her true guiding lights.

Another break followed, before 2017’s Something Else, which saw them stripping back and reworking some of their most classic tracks with the help of a string quartet from the Irish Chamber orchestra. To add to the sentiment of the project, they recorded it in Limerick, making it the only album they completed in their hometown. What the end result foregrounded was the fundamental power of their melodies. “If anything, I’d never write songs like those early ones now, as it’s too easy” says Noel. “But I think their simplicity is what attracted people to them.”

It was accompanied by an acoustic tour, during which Dolores and Noel got the writing itch again. Then, when Dolores’ back problems meant the group sadly had to cancel the rest of their live dates, the pair started working in earnest. “She went back to New York, where she was living at the time, and I went to France to meet up with my family, but they weren’t there yet, so I was on my own for a few weeks,” recalls Noel. “We were both bored and I said ‘why don’t we see if we can write an album and use the time productively?’ and that’s what we did.” Over six months, in the second half of 2017, the two of them came up with the songs that have now gone on to form their final collection ‘In the End’.

In shock after Dolores’ passing, Noel and the rest of the band eventually began to look through the vocal demos that she had already recorded for the album. One thing was for sure, though: they weren’t going to release anything unless it could truly honour her by standing up as a brilliant piece of work in its own right. Thankfully, after some digging, they realised they had the material to make that happen. “There were bits that she had done but hadn’t sent to me so you’d have a verse and chorus but then no second verse and you’d think ‘it’s such a pity’”, says Noel. “But then Dolores’ partner came over with a hard drive and he had all these other bits she hadn’t had a chance to send, so we ended up with full songs.” And it helped, of course, Dolores was such a naturally virtuosic singer. “Even on a bad day, she clearly gave a great vocal performance.”

Produced once again by Stephen Street, In the End sees the band coming full circle, with a collection that evokes their very first LP. “When we listened to the demos, the three of us and Stephen were thinking ‘this sounds much closer to the first album than anything else’. Dolores was singing very softly on some songs, which was closer to how she would have sung back then, and the simplicity of some of the songs as well brought us back to that time,” says Noel.

Certainly, it’s an album that, tune after tune, snags immediately. It kicks off with a formidable one-two which is a reminder of their range. The driving All Over Now is a classic, widescreen Cranberries anthem, with Dolores giving voice to the fractures of a relationship against a backdrop of chiming guitars; then, following it, the haunting string-swept ballad Lost dials the tempo right down, while giving space to Dolores’ yearning vocals to soar to soul-piercing heights. Elsewhere, they veer from the grungy release of Wake Me When It’s Over to the tender, country-inflected A Place I Know and the upbeat jangle-pop of The Pressure.

If there’s an overall lyrical theme, it’s a sense of wiping the slate clean, and new beginnings, which reflected where Dolores was, both in her personal and her creative life: re-energised and ready for a new phase. “I remember talking to her that summer and she said ‘I’m starting all over here’ and a lot of the songs discuss that,” says Noel. But, as ever with The Cranberries, lyrics that may derive from individual experience masterfully tap into universal emotions, framing them in terms that we can all relate to, whatever age, gender or nationality.

As the huge wave of public adulation in the wake of Dolores’ passing showed, The Cranberries may be over, in one sense – but they will forever live on in the musical pantheon.